A few years ago I bought a Haylou Smart Watch 2, my first smartwatch. It got to be quite useful for tracking my heart rate and sleeping times, but I quickly started wondering… how does it actually work? My curiosity immediately kicked in, and I spent quite some time reversing its functionality and compiling all findings in this repository.

This post briefly covers the journey of reverse-engineering this smartwatch. Enjoy it ;)

Reverse-engineering a smartwatch

As you may expect, reverse-engineering such a smartwatch is far from trivial. I would need some sort of vulnerability or exploit just to have some chance to dump the watch’s firmware, which felt way beyond my abilities. This is why, from the start, my goal was to investigate its Bluetooth functionality, something less far fetched but more reasonable for my abilities, still a fun challenge to get into.

This smartwatch has an official Android application, a truly terrible one. I couldn’t even get to register in the application without it crashing, and I was not the only one experiencing that: the application’s Play Store reviews were filled with users complaining about similar issues…

I searched for another application to control the watch, and soon enough I found Hello Haylou. Although it explicitly gatekeeps certain functionalities for the premium version, it worked fine. The app even supports around 10 different Haylou smartwatch models, but this RE-ing project is exclusively focused on the LS02 model, the internal model name for the Haylou Smart Watch 2.

I decompiled the Java source (for what I like to simply use this great online decompiler) for both applications and started inspecting them, only to find that the official application was even worse than I thought. Most of the code was not in Java but in native libraries - which I could just pop into IDA and try to get something out of them - but then it got even worse: said native code was doing some sort of emulation of a blob of… maybe PPC code it had embedded? God, why so much chaos for obfuscating such a broken app?

Surfing through Bluetooth GATT

Luckily for me, the unofficial app was far less chaotic and more reasonable to be inspected, although it still contained obfuscated package and class names, like release Android apps typically have. From this point, it was a matter of cleverly finding any Bluetooth-related code.

I started looking for any classes which imported Android Bluetooth classes/types. This eventually led me to two relevant classes, <obfuscated-terms>.tiborsosdevs.tibowa.MiBandSupport and <obfuscated-terms>.tiborsosdevs.tibowa.LS02WatchHandler (yeah, the class names were surprisingly not obfuscated).

This and many other smartwatches work using Bluetooth GATT. They provide a list of services via Bluetooth’s GATT protocol, where each service contains a list of so-called “characteristics”. Think of these as communication channels between the phone/device and the smartwatch. Both services and characteristics are identified by UUIDs, and luckily I was able to list all the ones provided by the smartwatch when I got to test my findings. After connecting through one of these characteristics, the smartwatch may send raw data bytes to the device, and vice versa, depending on the characteristic type.

There are a few different GATT characteristic types: Indicate, Notify, Read, Write, WriteWithoutResponse… for the LS02 smartwatch, the relevant characteristics are Read+Write, Read+WriteWithoutResponse or Notify.

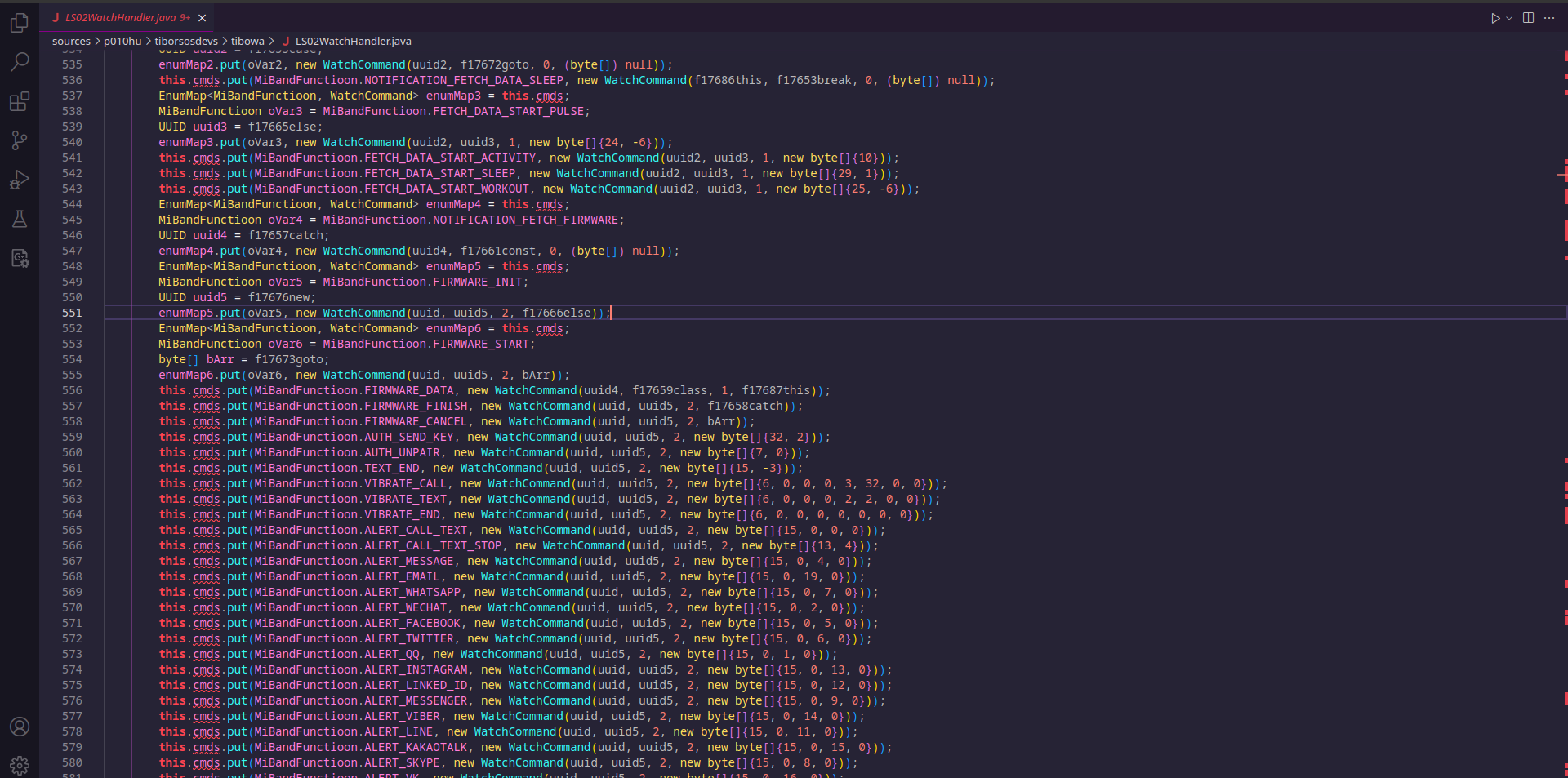

The LS02WatchHandler class contained the UUIDs of the relevant characteristics used by the smartwatch as static strings. Moreover, by navigating through some interesting classes which were referencing this class, it was a matter of time until I found some byte arrays which seemed to be the plain data sent via GATT characteristics:

After tracking their usage, finding the code actually dispatching raw data (which annoyingly was not properly disassembled, yet I was able to understand it through the Java bytecode output) and putting a quick code to test it, I was indeed sending and receiving data from the smartwatch.

Device ↔ smartwatch communication

I performed my initial tests in a custom Android app, almost copying their Bluetooth setup. It didn’t take me long to notice that I could just be using a PC program for testing, instead of annoyingly inspecting output logs of my Android app. I conveniently picked Rust for this task, whose crate system simplified a lot having to deal with Bluetooth library dependencies. Keep in mind that I had never worked with Bluetooth on a dev/technical level prior to these experiments, so I was slowly digesting the functionality and concepts of the GATT protocol while I was starting to find promising stuff on the reverse-engineered Java code. I had never touched any kind of Bluetooth libraries for development before.

My first tests, of course, were trying to send the simplest possible commands. The first step was to pair the device, in order for the smartwatch to recognize me. As can be seen in the screenshot of the RE’d Java code above, pairing seemed to be performed by sending a two-byte command {0x20, 0x02}. This was likely the first command I tried, and the result probably sparked a “eureka” moment in me: after the pairing is performed (which just requires sending that command), the smartwatch begins sending a lot of commands periodically with watch information.

Ironically, I was actually sending a badly formatted command. The command should be of the form {0x20, 0x02, <pair-key>}, where the pair key consists of 4 extra bytes of the unique key characterizing the pairing. By sending a smaller data array, these expected 4 bytes were treated as 0xFF by the watch by default, so I was essentially pairing with a (0xFF, 0xFF, 0xFF, 0xFF) key. This was still a successful pair, since the command seemed to work fine. The reversed code probably does it correctly by appending some key after the base command, but I haven’t really looked into it.

What about the other commands? For instance, one simple type of command contains the current battery level: it consists of a two-byte command {0xA2, <battery-level>} where the battery level value is the battery percentage sent as a byte (for instance, a 69% level would be indicated when receiving {0xA2, 0x45} from the watch). This command is always sent to the device after pairing, and is also sent each time the battery percentage changes. Other commands are also sent periodically without prior request, such as the recorded step count (distinguishing between steps done walking and running), heart rate and so on.

There are quite a lot of commands used by the smartwatch, where only a handful of them are briefly explained in this post for clarity/as a few examples. A detailed list of all reversed commands, along with basically everything I’ve reverse-engineered about this smartwatch, can be found in my RE docs.

One of the most satisfying commands to document were notification commands. These are used by the device (aka the Android app connected to the smartwatch) to notify the smartwatch when a certain app has notifications on the smartphone, like WhatsApp or Facebook messages. This is only used for messages and email, since phone calls are handled with different commands. These commands work in bulk, due to limitations in the data sizes that can be sent at once using GATT. The text message of the notification is split in chunks of max. 22 characters (although I recall finding that the reversed code uses a slightly smaller chunk size for some reason) and multiple commands are sent with the message pieces, starting with an initial command and ending with a final command to indicate start and finish of the long command sequence respectively.

Other commands use a similar technique of splitting their content into multiple commands as well, such as when retrieving the heart rate registry (the results of the last hours are sent in separate chunks).

Experimenting with watch commands

After I felt I had tested a good amount of the commands found in the reversed code, I was wondering if there were any commands that these non-official devs didn’t even know. By this point, I switched from testing commands found in their code to sending experimental command combinations, extra bytes, weird values… just to see how the watch reacted. This is, in fact, how I found out about the pairing key aspect mentioned above. By sheer trial and error I was able to get a better understanding of the command parameters than what the reversed code was doing. After all, this is way more fun than having to try to understand obfuscated and sometimes not even correctly disassembled Java code. This is how the largest part of my reverse-engineering docs were filled, since playing with commands and even with previously untouched characteristics led me to discover new weird commands being periodically sent through those alternative channels.

Current state

I eventually got a new Xiaomi smartwatch not so long ago, which partially explains the decline of motivation towards this project. Moreover, since this is not a well-known smartwatch (let’s be honest, it’s a cheap smartwatch from some random Chinese manufacturer) there is not such a big interest in continuing the work for others who might find it useful.

I have tried doing the same with the new Xiaomi smartwatch, but i haven’t been able to find anything. Commands appear to be either compressed or encrypted, and the disassembled Java code is not as easy to navigate as the one from Hello Haylou.