On my current voyage reverse-engineering Mario Kart DS (EU version for now), a while ago I decided to check what some MKDS cheat codes did so I could match them to my reversed code, in order to verify some of my current work and to maybe even give me hints of still undocumented stuff.

One of the various cheats codes I checked - one simple to explain - is 023CE2E0 07FFFFFF, which instantly unlocks everything in the game. According to cheat code specs I found - which took me a while to find - it was writing the 32-bit value 0x07FFFFFF at address 0x023CE2E0.

This was strange to me. The ARM9 code I am reversing goes in the console memory region from around 0x0200000 to 0x02180000, the ARM7 code goes from around 0x02380000 to 0x023A8000 and the region where MKDS overlay code is loaded goes from around 0x02180000 to 0x021C0000.

Where the heck is this writing to?

The answer happens to be related to how conveniently MKDS’s ARM9 code manages heap allocations on its available RAM.

Surfing the heap

Like virtually any modern program, MKDS uses dynamic memory allocation to allocate most of its more relevant global structs/objects. The SDK code does not use it internally whatsoever, but provides the interface for it to be used in games.

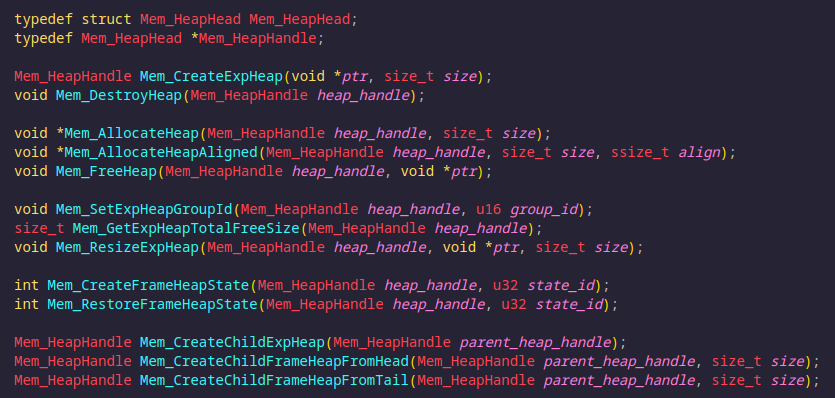

Such an interface works with heap handles, the allocator objects. Two kinds of heap handles are used: exp heaps, which work more like modern/typical allocators, and frame heaps.

Exp heap handles partition memory in blocks which are marked as free or used. This information, along with the heap handle’s data, is stored in small reserved sections of the available heap memory. When data is allocated, the exp heap searches for a free block where it can fit the data with the given constraints. The first obvious constraint is the desired size to allocate, but additional constraints are the optionally desired alignment - and otherwise defaulted to 4 - and the internally set allocation type.

Particular alignments may require additional space to ensure the resulting address is aligned as desired. The allocation type, on the other hand, specifies the free block choosing criteria: whether to choose the first block which satisfies all previously discussed, or whether to keep iterating until the best fit is found, hence the smallest candidate block. When allocated, the block is split into a free block with the still unused memory and a new used block with the just allocated memory.

A freshly created heap starts with a single free block covering the entire memory, and as more data is allocated more blocks get split. When memory is freed, the corresponding block is marked as free so it can be used by other allocations, thus making proper use of freed and unused space.

The frame heap is notoriously different. Data is allocated without going back - hence there is no concept of freeing allocated memory here - unlike the exp heap procedure.

Both heaps share a basic common interface and particular features. Exp heaps have group IDs, which is a particular value stored in used blocks for exp heaps and in frame states for frame heaps, which can be used for debugging purposes to track under which group ID value were certain allocations made. Frame heaps have a particular feature known as states. These resemble emulator savestates, where a snapshot of the current memory position - thus where the next allocation will happen - is saved and can be restored later.

Anyone who has done any reverse-engineering with the Nintendo Switch SDK library will find this explanation somewhat familiar: indeed, memory allocation is done almost identically in the DS and the Switch despite being generations apart. By comparing reversed code of both consoles, heap allocation routines are almost identical. They do have some differences nonetheless. Sanity checks are a major difference… because the DS code has virtually none of them. No bound checks, no null pointer checks, nothing whatsoever. The Switch heap code contains tons of them, on the other hand.

Down to the arena

After giving up on this cheat code dilemma for a while, I came back and decided to manually check different relevant global objects on my IDA database in case any of their fields could be related to unlocked secrets in the game. I didn’t even get to test this, since I suddenly realized that the memory address the cheat code was trying to write to could be heap memory, thus dynamically allocated data.

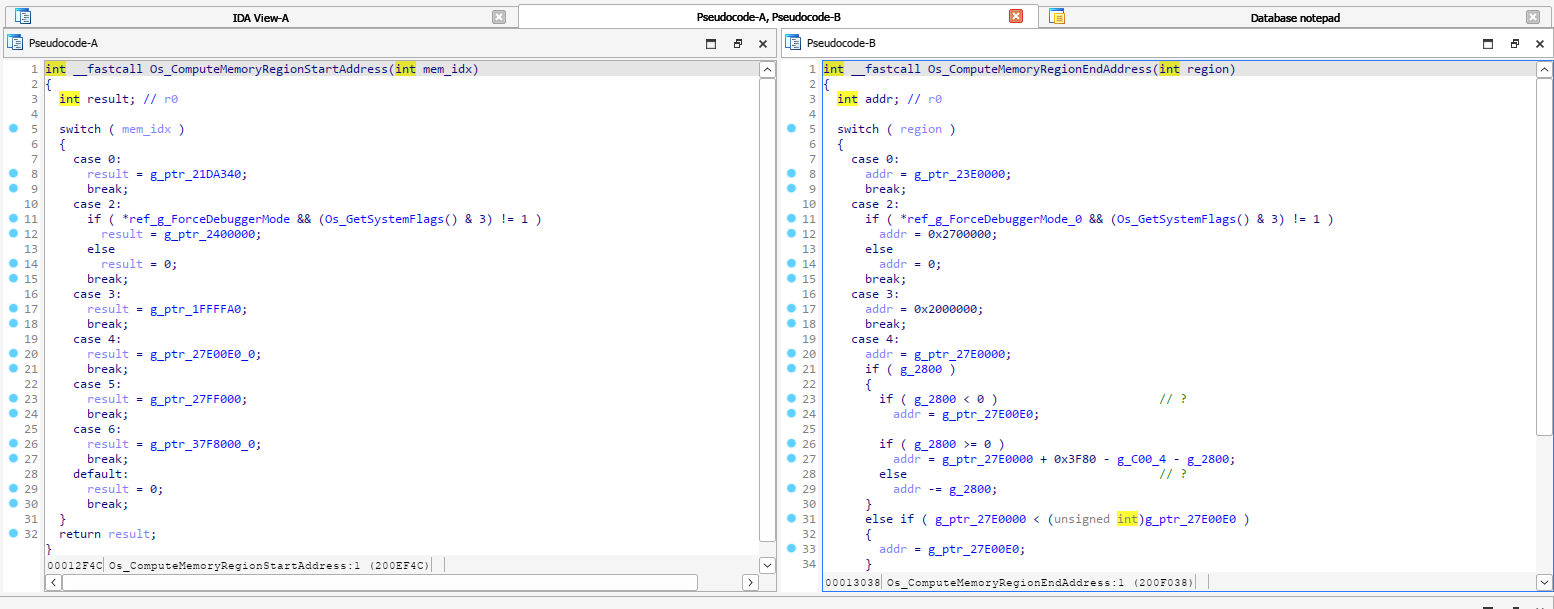

Every DS game - as part of the SDK initialization code - has two particular subroutines to determine the size - the start and end address, respectively - of several memory regions. Some of them have particular uses - such as TCM - but the relevant one here is the remaining RAM not containing any of the main ARM7/ARM9 binary code. This subroutine is essential for ASM hacking, since it contains the ranges of all key memory regions:

By checking this subroutine - which I already had reversed in some detail - I verified my suspicions, since the heap region goes from 0x021DA340 to 0x023E0000.

However, this still does not clarify the main mystery: how would I find what global object was being accessed by the cheat code at that address?

Determinism in memory

In any modern program using heap allocations, the resulting memory address - if, for example, its value were printed - will be something virtually random. This is because of two main reasons: one deeply rooted in the operating system - ASLR - and the result of more complicated control flows - overall non-determinism in memory allocations.

ASLR - address space layout randomization - is not relevant here: all modern operating systems randomize the - typically virtual - memory region designated to a process when it is launched explicitly so that they are not predictable, thus preventing any attacks or data breaches from outside programs. The DS does not have such protections: remember that I already mentioned the fixed, exact memory regions where MKDS’s ARM7 and ARM9 codes are loaded on game boot.

Think about a mildly complex program: all the loops, conditional branches… any slightly detailed program can be in a lot of states at any time, and if the program happens to make frequent use of heap allocations, even in the absence of ASLR the state of the internal heap allocator will be practically arbitrary. However, MKDS happens to be a wonderful exception for some cases.

First of all, the game happens to create a lot of child heap allocators throughout different parts of the code: a decent memory chunk of the heap is allocated, then used to create a child memory allocator there. This partially relaxes the potential arbitrariness of heap allocations, since by splitting the heap into sub-heaps less allocations will be made per heap than if a single global allocator was used - like in C/C++ standard libraries.

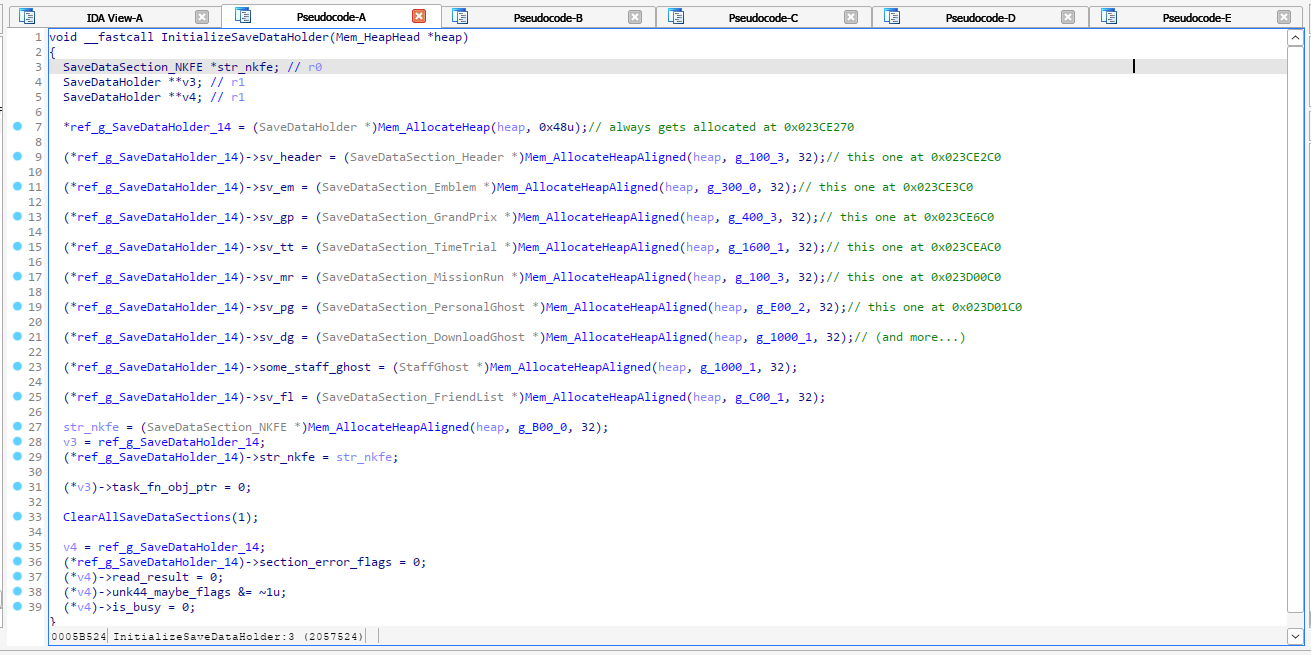

Following this, the fact that certain parts of the game happen to make just a few and easily trackable heap allocations of large, global objects - despite there being other parts of the code, like sound-related logic, which are quite the opposite - just happens to always allocate some key global objects in the exact same heap addresses:

These are the objects in question, which contain all savedata-related content. Since all the allocations always happen to follow in the same predictable order, they always end up in the same memory addresses.

One may notice that the cheat code itself hinted at the solution: it always writing at the same heap address regardless of being part of dynamically allocated memory, which means it is a predictable allocation - it is literally always allocated in the same address - hence memory allocations should be deterministic somewhere, and not in any place but in the allocation of some relevant object containing some unlocked secret stuff.

Of course, the original author of the cheat code doesn’t need to know this at all. They probably found that the value at said address was related to unlocked content in the game, checked what value a 100% completed game had there, and made the corresponding cheat to force that value.